After shutting down, why more New Orleans restaurants are starting to return

Cochon Butcher reopened after a hiatus to become a takeout and delivery hub for the Link Restaurant Group. The muffuletta makes a dashboard dining lunch after a quick pick up.

Juan’s Flying Burrito in Mid-City has reopened for take out after a hiatus. Stronger adherence to social distancing measures in the community was the reason.

Cochon Butcher reopened after a hiatus to become a takeout and delivery hub for the Link Restaurant Group. The muffuletta makes a dashboard dining lunch after a quick pick up.

Theo’s Neighborhood Pizza reopened for take out after a hiatus. Stronger adherence to social distancing measures in the community was the reason.

Theo’s Neighborhood Pizza reopened for take out after a hiatus. Stronger adherence to social distancing measures in the community was the reason.

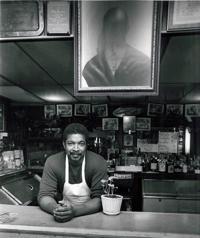

Barrow’s Catfish is known for its fried catfish platters, a tradition dating back generations for the Barrow family. The Hollygrove restaurant is continuing takeout service in the pandemic crisis.

Barrow’s Catfish is known for its fried catfish platters, a tradition dating back generations for the Barrow family. The Hollygrove restaurant is continuing takeout service in the pandemic crisis.

Cochon Butcher reopened after a hiatus to become a takeout and delivery hub for the Link Restaurant Group. The muffuletta makes a quick pick up lunch.

Barrow’s Catfish has a recipe for cayenne-flecked catfish perfected over generations and a family legacy of perseverance that goes back to one of the city’s longest-running African American restaurants, Barrow’s Shady Inn.

To find a path forward in the coronavirus fight, however, co-owner Deirdre Barrow Johnson had to write a new playbook, and she had to close Barrow’s Catfish for a stint to make it happen.

“We needed to make sure our priorities were in the right place, that what we were doing wasn’t just about business but about what’s best for our family, our employees and our community,” said Barrow Johnson. “We decided we needed to take some time to think about it and regroup.”

The Hollygrove restaurant closed for two weeks before reopening around Easter. Now it uses a hybrid carhop model, as staff wearing masks, gloves and reflective safety vests shuttle phone-in orders to customers waiting in their cars.

“We had to find a way to provide our service in these times,” Barrow Johnson said.

Staff photo by Ian McNulty

It’s been a month since Louisiana ordered many types of businesses to close outright in the effort to slow the pandemic’s spread. Restaurants, however, were given an option to stay open with takeout, delivery and drive-thru service.

Since then, restaurant owners grappling with how to continue have sometimes found their own answers changing. Some that initially embraced takeout later shutdown, often citing concerns for following social distancing mandates while remaining open in any capacity.

Now though, some are beginning to reopen after recalibrating operations, getting feedback from staff and, importantly, watching the behavior of the public. They’re also making bets about the future.

“In the two weeks we were closed, I think more people finally heard the message,” said Jammer Orintas, co-founder of Theo’s Neighborhood Pizza, which reopened its five area pizzerias in mid April.

“They’re more cautious about going out, they’re wearing masks, I think most people get it,” he said.

That wasn’t the case in March when Theo’s closed, a decision Orintas said was directed by the staff. Many were unnerved by customers who did not heed public health warnings.

“We were willing to stay closed longer if our employees weren’t comfortable coming back,” he said. “But we heard from enough employees who were ready and our customers were calling out for it.”

Nimble by necessity

Restaurants have had to adapt quickly and constantly during the crisis.

In the span of just 11 days last month, the Link Restaurant Groupshifted from busy dining rooms to takeout only, then changed to a consolidated menu at one location and then eventually shut down.

But on April 15, the company got back into business, making its meat market/sandwich shop Cochon Butcher into a one-stop portal for a combined takeout and delivery operation, drawing dishes from sister restaurants Cochon, Pêche Seafood Grill, Gianna and Herbsaint, which all remain closed. The company’s Uptown bakery café La Boulangerie also reopened.

“The most important thing for takeout is to be here for the community, to give some sense of normalcy,” said company co-founder Donald Link.

Even while shut down, Cochon has been home base for an ongoing effort to feed laid off staff and other hospitality workers. That program increased the company’s confidence with running kitchens with smaller crews, spread out to minimize contact, and it helped refine customer pick-up procedures.

“We’ve been watching the conversations nationally about how we get back to business eventually,” Link said. “We can start doing things now so we’ll be in a better position to come back later.”

With no clarity on when something closer to normal business might resume, getting back to business under any terms is also a survival strategy, keeping some staff working and the gears of restaurants turning.

Juan’s Flying Burrito began reopening its locations in mid April, first with its Mid-City restaurant and its two Magazine Street locations to follow.

“It’s not about money, no one’s making a profit now, it’s about remaining viable and contributing in some way during all this,” said co-owner David Greengold.

Juan’s also closed amid concerns that customers were not following social distancing precautions. Greengold said that as other businesses, like groceries, began to regiment better protocols, he felt more people were embracing the “new normal” and that his restaurants could reopen on different terms.

That included setting up online ordering systems and moving prep work for all the restaurants to one kitchen to minimize staff in close kitchen quarters.

“It’s weird for everyone because restaurants like ours are normally highly social environments, it’s hard to break that,” he said. “We had to take some time to figure that out and for people to learn what they have to do for this to work.”

File photo by Lionel M. Cottier, Jr. / The Times Picayune archive

At Barrow’s Catfish, Barrow Johnson is seeing many of her old customers pulling into the parking lot again, ready for more of the catfish plates her grandparents and parents made famous at Barrow’s Shady Inn. In business from 1943 until Hurricane Katrina, it was the inspiration for her new restaurant, which she and her family opened in 2018.

For the uncertainties now, she looks to their example for encouragement.

“We’re drawing on our strength from the past, from what we’ve been through and endured,” she said. “When people ask how they’re going to keep going, I say you keep doing what you do best.”